Confederate Stan’s Monument Protection Bill Is A White Supremacy Power Grab

Stan Gerdes wants to keep racist monuments standing with a bill that locks in the legacy of Jim Crow.

A lot is going on at the Texas Capitol this week. The Senate is charging forward with bills that attack abortion access and criminalize basic reproductive healthcare. And while those deserve every ounce of our outrage, I want to talk to you about something that didn’t make the headlines, a bill from Representative Stan Gerdes (R-HD17), better known around here as Confederate Stan.

His bill would make it nearly impossible to remove Confederate monuments and other tributes to white supremacy from public property, even in communities that want them gone. It would require a two-thirds vote from the Texas Legislature, or a countywide election, for any statue older than 25 years to be moved. In most rural Texas counties, that means never.

This one hits close. I grew up in the big city, where my father warned me about venturing too far into the Texas backwoods. He’d say it was “Mississippi over there” when it came to matters of race. He wasn’t wrong. The first time I started traveling to these rural towns, I was stunned by what I saw: statues glorifying the Confederacy standing proudly on courthouse lawns, the very places Black Texans were once denied justice. I wanted to know how they got there. That question changed my life.

Years ago, on an old blog, I started writing about these monuments: the one in Cooke County, where the largest mass hanging in American history took place, 42 suspected Union sympathizers executed during the Civil War. The one in Weatherford, perched on top of the town well, where lynched Black men’s bodies were dumped. The broken statue in Kaufman was forced back onto the courthouse lawn in the 1950s after the Daughters of the Confederacy and local officials demanded it. That research is what pushed me to return to college to earn my history degree.

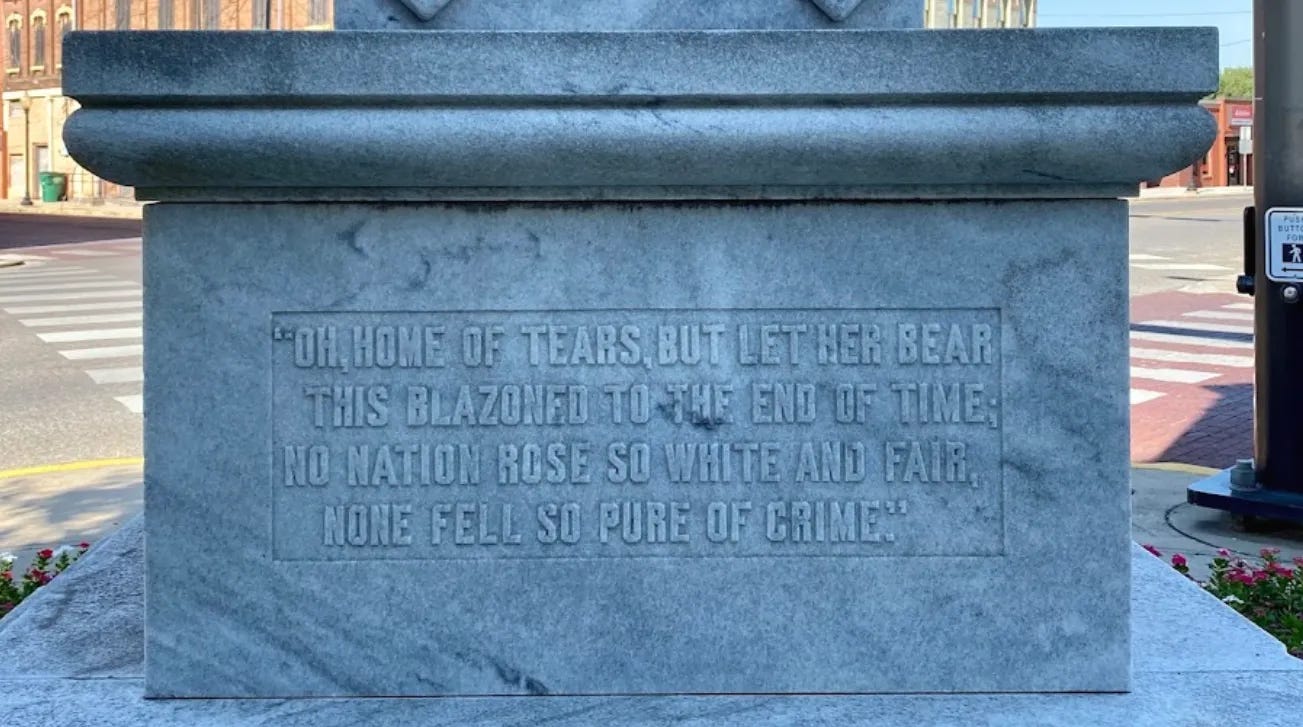

These aren’t just statues. They are threats carved in stone.

They were put there during Jim Crow, when Black Texans couldn’t vote. In many places, they were erected with the help of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Ku Klux Klan, working in lockstep. Their message was clear: this is white land, and justice here is not yours.

And it worked. Even today, in towns where these statues still stand, you’ll find the legacy of white supremacy embedded in everything from policing to political participation. Comanche County, once a sundown town, still has a Black population of less than 0.3% in 2025. Bell County, which has a Confederate monument on public land despite being majority-minority, rarely sees more than 50% voter turnout. That’s the reality Confederate Stan’s bill exploits. He knows these monuments won’t be removed, not when the deck has been stacked for over a century.

This isn’t preservation. It’s state-sponsored intimidation. And it’s a direct attack on the communities who’ve been silenced for generations.

Several people who testified in favor of this bill I recognize from rural protests and the County Commissioners’ Court, where they once identified themselves as members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy or the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Although they said they were representing “themselves” in this hearing, a quick Google search can confirm most of their affiliations, starting with Shelby Little, who spends every Saturday dressed in Confederate gray, standing on the Williamson County courthouse lawn.

So what’s in Confederate Stan’s bill?

This bill is about protecting old Confederate lawn ornaments from the indignity of ever being moved. Stan Gerdes’ bill (the one he probably drafted under the watchful eye of a bust of Jefferson Davis) splits monuments into two categories: state property and local property. But in both cases, it does the same thing, puts white supremacy under glass and slaps on a “do not touch” sign.

Monuments on State Property (like universities or Capitol grounds).

If a statue is on state-owned land, and it’s been around 25 years or longer, it cannot be removed, relocated, or even “altered for historical accuracy” unless you get a two-thirds vote in both the Texas House and Senate. Good luck with that.

If it’s younger than 25? The only person who can approve changes is whoever runs the agency that originally put it there. So again: you’d better hope the person who installed the Stonewall Jackson memorial in 2004 had a late-in-life moral awakening.

You can add a new statue nearby, one that “complements or contrasts” with the original. So sure, put up a statue of Harriet Tubman next to a Confederate general if you like, but don’t you dare remove the man who fought to keep her enslaved. That would be erasing history (but only the white kind).

Monuments on County or Municipal Property (including courthouses).

Here’s where things get even more cynical. This part is about county courthouses, city halls, parks, bridges, and public squares, the places where most Confederate statues still sit, smug and unbothered.

If a statue has been on public land for 25 years or more, it can only be removed if a majority of the county or city votes for it in an official election. So if you’re in a county like Bell or Comanche, where white supremacy left generations of Black voters disenfranchised and disillusioned, guess what? That statue is going nowhere. The same systems that kept people from voting are now being used to keep racist monuments in place.

If the statue is under 25 years old, it can be removed by a vote of the county commissioners court or city council, but don’t get too excited. Most of these Confederate relics are 100 years old.

And if a local government removes one anyway?

Here’s where Stan gets petty. If a town dares to remove a statue without going through the new approval maze, any local resident can file a complaint with the Attorney General, saying: “Dear Ken Paxton, the statue of the Condeferate rapist who owned and trafficked 87 people is missing. Please punish the people who moved him.”

Then the AG can sue the county or city, and if a judge agrees? The local government pays up:

$1,000–$1,500 for the first violation

$25,000–$25,500 per day after that

Each day the statue stays gone is a new fine. You heard that right, the town could be fined $25,000 a day for not having a Confederate statue on its courthouse lawn. Meanwhile, they’re still trying to get clean water to half their residents and fix a collapsing roof on the library.

Oh, and by the way? The bill waives sovereign immunity. Meaning counties and cities can be sued for this, and can’t claim legal protection. The same legislature that hides behind immunity when they mess up now wants to leave your small town legally naked because it dared to move a racist rock.

What does this bill really mean?

This isn’t about “preserving history.” It’s about preserving power, specifically, white supremacist power structures that were built into the foundations of rural Texas and cemented into stone.

These monuments were never neutral. They weren’t placed by some dispassionate committee of historians after careful review of the past. They were erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Ku Klux Klan at the height of Jim Crow, when Black Texans couldn’t vote, hold office, or walk safely into a courthouse, let alone demand their history be recognized.

They were acts of psychological warfare. They sent a message: “This land belongs to us. Justice here is not for you.”

And for generations, that message stuck. In counties like Comanche, where the population is still over 95% white, or Bell County, where Black and brown families face higher rates of stops, arrests, and school discipline, these statues are part of a larger system that says: You do not belong here.

Stan Gerdes and his allies know exactly what they’re doing. This bill doesn’t just freeze racist monuments in place. It weaponizes them. It punishes small towns for trying to move forward. It discourages any local effort to reckon with the past. It tells Black, Latino, and Indigenous Texans that you may have the right to vote now, but your voice still doesn’t count.

That’s the Texas they want. A state where it’s easier to fine a town for taking down a Confederate statue than to pass a bill ensuring clean water or fair housing. A state where white supremacy gets taxpayer-funded legal defense, and the communities who’ve suffered under it get told to hold an election and cross their fingers.

But I believe in a different Texas. One where we tell the truth about our past, even the ugly parts. One where no child has to walk past a statue of a man who would have sold them for profit. One where we get to decide what justice looks like, not the ghosts of Jim Crow and the men who serve them still.

What you can do:

This bill is currently moving through the committee, and your voice can make a difference. Call the committee members and tell them to vote NO on Stan Gerdes’ monument protection bill, HB3227. Be polite, but be firm.

Remind them: local voters, local councils, and county commissioners, not big-government lawmakers, should decide what stands on local property. If a community wants to have a conversation about its public spaces, it shouldn’t have to beg the Texas Legislature for permission. That’s not freedom, that’s authoritarianism in boots.

Republicans love to talk about small government and local control, until it threatens their grip on power. Then they come running with fines, lawsuits, and mandates from Austin. This bill is no different. It’s about keeping their control.

Be respectful. Be direct. And tell them to leave decisions about local property where they belong: with the people who actually live there.

Committee members:

Chair Will Metcalf (R-HD16) - (512) 463-0726

Vice-Chair Lulu Flores (D-HD51) - (512) 463-0674

Sheryl Cole (D-HD46) - (512) 463-0506

Mano DeAyala (R-HD133) - (512) 463-0514

Helan Kerwin (R-HD58) - (512) 463-0538

Trey Martinez-Fischer (D-HD116) - (512) 463-0616

Angelina Orr (R-HD13) - (512) 463-0600

Cody Vasut (R-HD25) - (512) 463-0564

Charlene Ward-Johnson (D-HD139) - (512) 463-0554

Final thoughts.

These days, I spend most of my time focused on politics, on legislation, elections, and the nonstop chaos coming out of the Texas Capitol. But anti-racism work doesn’t stop just because the news cycle moves on. And I will always speak out against these monuments to white supremacy and the systems that protect them.

This bill may look like just another piece of bad legislation, but it’s part of a much bigger pattern and a desperate effort to keep the past buried in stone and the future locked out of reach. I became a historian because I wanted to understand how these monuments got here. I became a political activist because I want to make sure they don’t stay.

Confederate Stan can try to write Confederate history in law. But we’re still here. We know the truth. And we won’t be quiet.

May 3: Local and County Elections

June 2: The 89th Legislative Session ends.

June 3: The beginning of the 2026 election season.

Click here to find out what Legislative districts you’re in.

LoneStarLeft is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Follow me on Facebook, TikTok, Threads, YouTube, and Instagram.

I have finally made the time to call everyone in the committee. 😅

One “R” office asked me if I was the Texas Supreme Court Justice. 😂 Not unless she is a “D!” But I know about her. It started when a “friend” said they voted for me. Then they learned I am a Democratic Party person (for life!)

I also plan to call my “R” so call people who represent me, When it gets on the floor. Please let us know if it does. UGH. Republicans should be saying “ This is overreaching. But they will not because it’s their idea”. 🤬

I’m feeling overwhelmed. How do you keep up with this! 🙏🏼

It was confederate history month (april), and I kept seeing celebrations from other states on FB. It was eerie, weird, regressive, and outdated.

I guess in the past, they would celebrate locally but now with social media the whole world can see how silly it looks. We have to let the light shine on the darkness.